Disruptive innovation in Government – A Case for i-county council

The Conservative Party election manifesto mentioned promotion and funding in innovation strategy in five areas: 1) Motor industry in the Midlands; 2) Ari-tech and high tech industry in the east of England; 3) Britain as a technological innovation hub; 4) Healthcare life science industry; and 5) Policing innovation to transform public relations using technology. The manifesto states: ‘We will devolve powers and budgets to boost local growth in England and we will deliver more bespoke Growth Deals with local councils, where locally supported, and back Local Enterprise Partnerships to promote jobs and growth’.

One method of achieving these manifesto goals is to promote ‘disruptive innovation’ in Government. In 1997 Clayton Christensen published his now famous book The Innovator’s Dilemma, in which he coined the term disruptive innovation as a product or service that takes root initially in simple applications at the bottom of a market and then relentlessly moves upmarket, eventually displacing established competitors. This concept appears to fit into the commercial world with real life corporate case studies.

Commercial Examples

Chinese and Korean carmakers have replaced Japanese carmakers for low-priced cars, making the latter move to the low volume luxury market. Outside the public sector, we’ve grown accustomed to steadily disruptive innovation; examples include auto rentals transformed by Zipcar; budget air travel by Easyjet; computing power doubling every 18 months, Netflix for sourcing entertainment, Tesla for electric cars, crowd-funding portals for venture capital; i-watch for more traditional time-keeping devices.

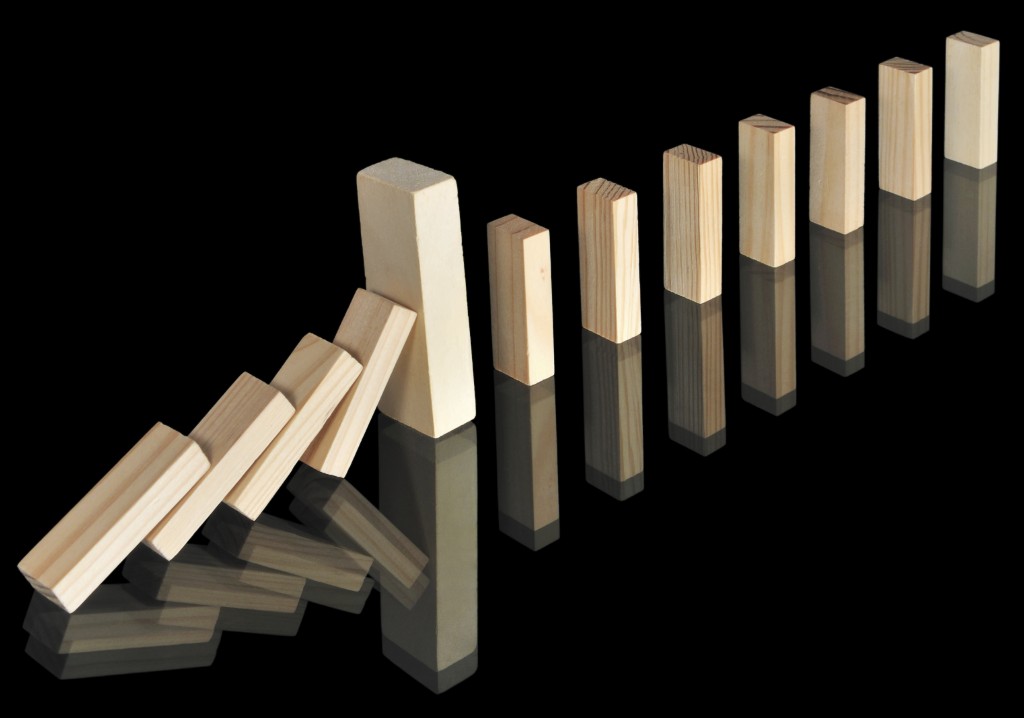

The disruptive innovation concept has been used to explain virtual disappearances of established businesses by smaller, nimble and low-cost entrants to the market which grow more sophisticated over time. The assumption is that companies tend to innovate faster than their customers’ needs evolve, and as a result these companies eventually end up producing products or services that are actually too complex, expensive and complicated for many customers in their market.

Disruptive Innovation in Government

Despite the evidence in commerce and industry, very little has been explored as to how this concept could apply to innovation in Government. I believe that disruptive innovation can thrive in Government. Creating the conditions for disruption will first require policymakers to view the Government as a series of markets that can promote more efficient, adaptable and less expensive public services. In order to cope with irrelevant and obsolete disruptive innovations, the Government will have to use nimble technology to challenge legacy large complex processes and systems used by Government departments and challenge their status quo.

Indeed, the ‘players’ more likely to help the Government will most often be small businesses at a local level, especially those SMEs which specialise in web-based technology and have a passion for customer service. Over time, given the opportunity and incentives, they will challenge the traditional well-embedded legacy technology and help to unravel centralised silo-driven Whitehall department bureaucracy.

Disruptive innovation is unlikely to come from the traditional management structures of Government or local authorities. Their way of operation and distribution channels does not allow or incentivise them to disrupt traditional methods. Take for example Ford and Chrysler developing electric cars in early 1990s. These companies were firmly positioned in the gasoline market and it was unlikely they would come up with a commercially disruptive technological solution. In the end, non-traditional manufacturers like Tesla overtook these traditional markers.

Case Study on disruptive innovation

According to a Which? Magazine report, HSBC’s First Direct subsidiary, which offers Internet, mobile and phone banking to its clients, always scores highly on excellence in customer experience and according to its CEO, their way of achieving this is to see the world from the customer’s point of view. When it was set up in 1989 by Midland Bank, it was one of the first entrants to the ‘no-branch’ banking business model. It was disruptive innovation that got First Direct going and it is a credit to HSBC to keep the independent model going.

Consider these practical ways of achieving these goals using a disruptive innovation hub.

Disruptive innovation hubs

Each LEP should create a disruptive innovation hub in partnership with local technology SMEs (Small to Medium sized Enterprises).

They will involve three main stages:

- Disruptive idea generation: The role will be to find out a disruptive hypothesis (defined by Luke Williams as ‘an intentionally unreasonable statement that gets your thinking flowing in a different direction’). This can get policy makers thinking in radically different directions and asking ‘what if’ would be essential. The idea generation should come from members of the hub and as such it should be a wider group of people from the community and local businesses with passion for customer service and technological bias. I propose that membership of the hub should not exceed 10 to keep it nimble.

- Disruptive idea development: Each hub would create a technology innovation register of no more than five projects, which they believe could radically change the service offering and achieve significant cost savings or economic benefits to local citizens

- Disruptive idea commercialisation: Each LEP Board should select the best small-scale disruptive innovation. I recommend offering equity stakes to the SMEs who participated in the hub and development of the product which can be funded by Central Government or Local Authority funding.

Pilot Study: Example of a Public Sector Disruptive innovation: Creation of i-County Councils

I propose the creation of an i-County Council, a stand-alone subsidiary of the existing local authorities with a budget and commercial revenue making opportunities. The model is similar to HSBC Bank’s independent First Direct subsidiary. They will be run as independent commercial subsidiaries whose management should build commercial partnership with small tech companies to develop disruptive innovative products.

The i-County Council will communicate solely by electronic methods with its local citizens. They should be tasked to come up with ideas to develop a range of apps for hand-held devices to communicate the status of public services. Each citizen will have a secure area within the web portal (a ‘dashboard’), which will be a ‘one stop shop’ to manage services such as council services, local health services, security, community services, retail opportunities etc. and this will aim to create a local community. This may involve creation of a tailored dashboard for citizens (e.g. health records, council services, local businesses) in a secure environment using artificial intelligence.

The i-County Council will have arms-length agreements with the parent (Local Authority or County Council) and they will have the ability to buy services from other neighbouring local authorities, if deemed economically viable.

Conclusion

In July 2015, George Osborne launched his spending review with £20bn cuts of Whitehall budgets with unprotected departments to draw plans to reduce 25% to 40% of their budget.

Such targets tend to be met with deep scepticism by the civil servants charged with actually figuring out how to do this. To get more for less requires doing things differently. This entails new business models, new entrants, new technologies, and the willingness to reduce or phase out existing practices. Disruptive Innovation offers a way accomplish this goal and, in the process, transform public services.